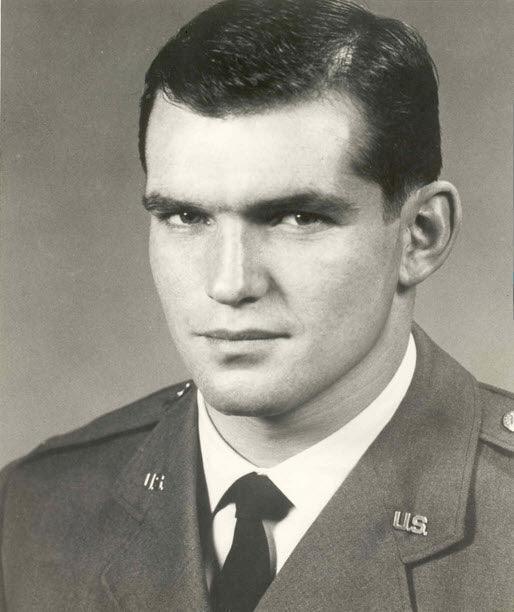

Maj. George E. Day - Code Of Conduct - Part 3

The Early Days

On February 24th, 1925, young George E. Day was born in Sioux City, Iowa. Day grew up in the Great Depression.

He struggled through his adolescent years and on his 17th birthday in 1942 Day did what many young men did during WWII. He dropped out of school and enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps.

After completing Marine basic training, he shipped out for the Pacific and spent the next two and a half years with the 3rd Defense Battalion at Johnston Atoll. He returned to the States in 1945 and with WWII over was discharged from the Marines.

Over the next four years, he earned an undergraduate and law degree and by 1949 was a practicing attorney.

On June 25, 1950, the Korean War broke out.

In 1951 Day was called to active duty, completed pilot training, and flew an F-84 Sabrejet for two tours in the Far East in the Korean War.

A photo of a USAF F-84 Thunderjet taking off for a mission in Korea. The aircraft was shot down 8-29-52.

Flying the Thunderjet

Typical of most early jets, the Thunderjet's takeoff performance left much to be desired. In hot Korean summers with a full combat load, the aircraft routinely required 10,000 ft (3,000 m) of runway for takeoff even with the help of JATO bottles for additional thrust.

All but the lead aircraft had their visibility obscured by the thick smoke from the rockets. F-84s had to be pulled off the ground at 160 mph with the control stick held all the way back.

Landings were made at a similar speed. Despite the "hot" landing speeds, the Thunderjet was easy to fly on instruments and crosswinds did not present much of a problem.

Misty FACs

Misty FACs (forward air controllers) flew at low altitude, spotting and marking enemy targets in heavily-defended areas in Laos and North Vietnam. This all-volunteer group had a quarter of their number shot down during these extremely hazardous missions.

U.S. Air Force FACs normally flew slow, propeller-driven aircraft to locate North Vietnamese personnel and supplies moving south along the "Ho Chi Minh Trail." As the communists reinforced their infiltration routes with antiaircraft artillery (AAA) and surface-to-air missiles, the loss rates over certain areas became unacceptable.

To resolve this problem, the U.S. Air Force decided to use faster, two-seat, jet-propelled F-100F FACs over the most heavily-defended spots under the code name COMMANDO SABRE. In June 1967 Detachment 1, 416th Tactical Fighter Squadron, commanded by Maj. George "Bud" Day, began operations.

The all-volunteer aircrews of this unit quickly became known by their radio call sign "Misty".

F-100 Super Sabres

A photo of a North American F-100 Super Sabre over Vietnam circa 1967.

Specifications:

- Two Seat Single Engine Swept-Wing jet fighter

- Wingspan: 38 feet 9 inches

- Length: 47 feet t inches

- Height: 16 feet 2.5 inches

- Empty Weight: 20,638 lbs

- Gross Weight: 38,048 lbs

- Top Speed: 892 mph

- Engine: Pratt & Whitney J57-P-21A 10,000 lbs thrust

Commando Sabre Operations Painting: Courtesy of David Tipps.

During their missions, Misty FACs often flew against the Ho Chi Minh Trail, focusing on its key passes from North Vietnam into Laos. They operated at relatively low altitude, constantly turning their aircraft to throw off the aim of enemy anti-aircraft gunners.

Misty FACs located and marked targets for other aircraft to hit, and they occasionally used their 20mm cannon to attack targets themselves. Misty FACs also spotted targets in southern North Vietnam and supported rescue forces to recover downed aircrew, often being the first aircraft on the scene.

In addition to being extremely hazardous, Misty FAC missions were exhausting for the aircrews. They remained on station for four to six hours, during which they left North Vietnamese air space multiple times to refuel from an aerial tanker.

In spite of their skill, specialized tactics, and fast aircraft, they paid a high price for striking at the vital, well-defended lifeline of the communists. Enemy ground defenses shot down nearly a quarter of the 155 Misty FAC pilots (and two were shot down twice).

The Vietnam War

In 1967, 43-year-old Maj. "Bud" Day volunteered for duty in Southeast Asia, and became commander of the Detachment 1, 416th Tactical Fighter Squadron, COMMANDO SABRE. This unit was better known by its radio call sign -- "Misty" -- which was Day's favorite song.

On August 26, 1967, Major George E. Day was airborne over North Vietnam on a forward air control mission when his F-100 was hit by enemy groundfire. During ejection from the stricken fighter his right arm was broken in three places and his left knee was badly sprained. He was immediately captured by the North Vietnamese and taken to a prison camp.

Major Day was continually interrogated and tortured, and his injuries were neglected for two days until a medic crudely set his broken arm. Despite the pain of torture, he steadfastly refused to give any information to his captors.

On September 1, feigning a severe back injury, George lulled his guards into relaxing their vigil and slipped out of his ropes to escape into the jungle. During the trek south towatd the demilitarized zone, he evaded enemy patrols and survived on a diet of berries and uncooked frogs.

On the second night a bomb or rocket detonated nearby, and Major Day was hit in the right leg by the shrapnel. He was bleeding from the nose and ears due to the shock effect of the explosion. To rest and recover from these wounds, George hid in the jungle for two days.

Continuing the nightmarish journey, he met barrages from American artillery as he neared the Ben Hai River, which separated North Vietnam from South Vietnam. With the aid of a float made from a bamboo log, he swam across the river and entered the no man's land called the demilitarized zone.

Delirious and disoriented from his injuries, George wandered aimlessly for severaf days, trying frantically to signal US aircraft. He was not spotted by two F AC pilots who flew directly overhead, and, later, George limped toward two Marine helicopters only to arrive at the landing zone just after the choppers pulled away.

Twelve days after the escape, weakened from exposure, hunger, and his wounds, Major Day was ambushed and captured by the Vietcong. He suffered gunshot wounds to his left hand and thigh while trying to elude his pursuers. George was returned to the original prison camp and brutally punished for his escape attempt.

On a starvation diet, the 170-pound man shrank to 110 pounds. He was refused medical treatment for broken bones, gunshot wounds, and infections. Renewing the pressure to force Major Day to give vital military information, the North Vietnamese beat and tortured him for two days.

Finally, he was bound by a rope under his armpits and suspended from a ceiling beam for over two hours until the interrogating officer ordered a guard to twist his mangled right arm, breaking George's wrist.

At this point Major Day appeared to cooperate with his captors, who felt that they had broken him at last. However, facing death if he was discovered, George deliberately gave false answers to their questions, revealing nothing of military significance.

Two months after his Super Sabre had been shot down, Major Day was transferred to a prison camp near the capital city of Hanoi. By this time he was totally incapacitated, with infections in his arms and legs and little feeling in his twisted hands. George could not perform even the simplest tasks for himself, but still he was tortured.

Almost unbelievably, his commitment to utterly resist every attempt to gain military intelligence never wavered. By withholding information despite the cost in personal suffering, George Day sought to protect fellow airmen who were still flying missions against the northern strongholds of the enemy.

He did not fail.

After five and one-half years of captivity, Colonel George E. Day was released with his comrades in arms, the American prisoners of war, on March 14, 1973.

A photograph of Maj. George E. Day upon his return from being a POW in North Vietnam.

The veteran pilot had flown over 5,000 hours in jet fighters. In addition to the Medal of Honor, he has won the Air Force Cross, Silver Star, Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with nine oak leaf clusters, Bronze Star for valor with two clusters, and the Purple Heart with three clusters.

Post Vietnam War

After being passed over for nomination to brigadier general, Day retired from active duty in 1977 to resume practicing law in Florida. At his retirement he had nearly 8,000 total flying hours, 4,900 in single-engine jets, and had flown the F-80, F-100, F-101, F104, F-105, and many other military jets.

Following his retirement, Day wrote an autobiographical account of his experiences as a prisoner of war, Return with Honor, followed by Duty, Honor, Country, which updated his autobiography to include his post-Air Force years.

Day died on 27 July 2013 surrounded by family at his home in Shalimar, Florida. He was buried on August 1 at Barrancas National Cemetery at NAS Pensacola, FL.

John McCain, Day's prisoner-of-war cellmate, said on Day's death, "He was the bravest man I ever knew, and his fierce resistance and resolute leadership set the example for us in prison of how to return home with honor.

View this video interview with George "Bud" Day:

I hope you enjoyed this trip through some of the history of aviation. If you enjoyed this trip, and if you are new to this newsletter, sign up to receive your own weekly newsletter here: Subscribe here!

Until next time, keep your eyes safe and focused on what's ahead of you, Hersch!

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.