The Shootdown of Tiger #620

Its 1956, and there is a lot going on in aviation.

Speed records were falling in the quest to be the fastest airplane in the world.

Supersonic flight had been acheived only 10 years earlier, and chasing more speed brought new challenges to pilots and aircraft designers, but also accompanied by new perils.

The F9F Cougar

Grumman Aircraft Engineering Company had manufactured the stock F9F 'Cougar' aircraft which featured advancements in aerodynamic science, such as adherence to the 'Aea Rule", reducing transonic drag and making it possible for the aircraft to achieve supersonic speeds.

A US Navy F9F Cougar in flight.

By 1953 the new design no longer resembled the Cougar and was sporting an all new redesigned wing replacing ailerons in favor of spoilers to control the roll of the aircraft.

They added slats to the leading edge of the wing to improve low speed manuevering, and a folding wing for storage on an aircraft carrier.

The aircraft was capable of Mach 1.1 at 35,000 feet due to the new Curtis-Wright Corporation Wright J65-W-18 turbojet engine with an afterburner.

The aircraft carried four hardpoints for AIM-9 'Sidewinder' air-to- missles along with four 20-millimeter Colt Mark-12 cannons capable of firing 125 rounds per gun.

The new aircraft was called an F11F 'Tiger", and in 1956 was undergoing test flights.

F11F 'Tiger' on a test flight by a Gruman Aircraft Engineering Corporation test pilot.

Feet Wet

Feet wet was a term used by Navy pilots when they flew the aircraft over water, and Feet Dry was called when back over land again.

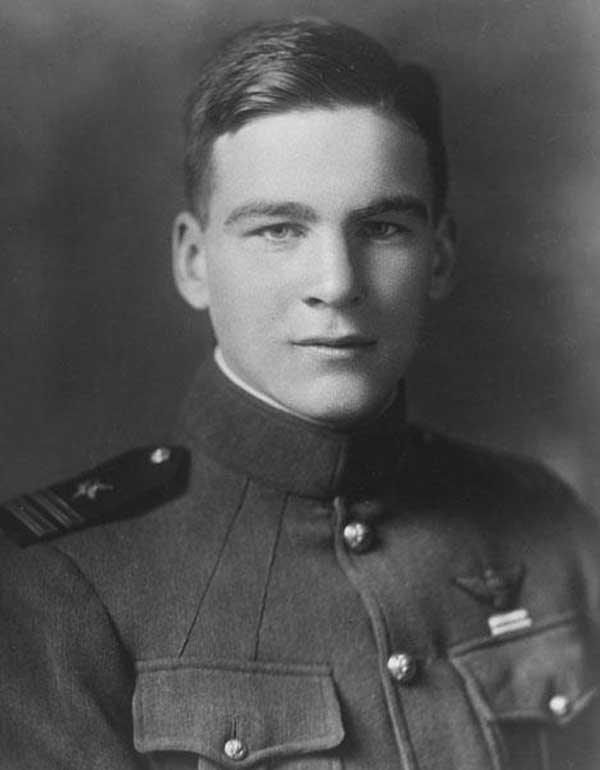

Grumman had a test pilot by the name of Thomas W. Attridge, Jr., a 33 year old former Navy aviator and father of three.

Tom was used to flying over water.

In 1942, upon graduationi for the elite Phillips Exeter Academy, Attridge joined the Navy as an Ensign and was sent to the Pacific where he flew Hellcats aboard the USS Belleau Wood (CVL-24) aircraft carrier.

Tom was part of air support of ground operations on Guam, followed by air strikes on targets on Palau and the Phillipines. In October he was involved in strikes on Okinawa, Formosa, Luzon and Leyte, and was part of the Second Battle of the Phillipine Sea.

The Test Flight

On September 1st, 1956, Tom was taksed with flying F11F 'Tiger" number 138620 on a test flight.

The test flight was to take place over a gunnery range 20 miles out in the Atlantic Ocean.

The flight plan called for Attridge to climb to 20,000 feet and then enter a shallow 20 degree dive and test the aircraft's 20-millimeter cannons and then level off at 7,000 feet.

He entered the dive and accelerated to Mach 1 and fired a short four-second burst at 13,000 feet, expending 70 rounds.

He entered a steeper dive and then fired the cannoncs again at 7,000 feet to clear the gun belts. Having just finished firing this second four-second burst the aircraft began to rattle.

The Tiger's windshield buckled inward, at Attridge assumed he had struck a bird.

He reported to the tower at the Long Island airfield that the only sign of damage he could see was to the cockpit windshield along with a sizeable gash on the outboard side of the right engines intake.

What worried Tom more was that he could only get 78 percent engine power. If he tried to increase power beyond that the engine would growl it's displeasure, and sounded like a Hoover vaccum cleaner picking up gravel from a rug.

Finally the engine gave out about 1/2 mile from the end of the runway, so he retracted the landing gear and made a dead-stick landing in the woods below.

A 'Million To One Shot'

The post-accident investigation revealed that he had not, in fact, struck a bird, but instead had been struck be a number of 20-millimeter bullets which struck the aircraft in a number of places including the engine inlet guide vanes, the engine intake, the windshield, and the aircraft nose.

Luckily, the rounds were not explosive rounds, like those used in combat, otherwise Attridge might not have survived.

An illustration showing how Tom Attridge's F11F Tiger flew into it's own canon fire, downing the aircraft.

According to Rear Admiral William A. Schoech, assistant chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics for Research and Development, the muzzle velocity of the shells was 3,000-feet a second. Their speed through the air (the muzzle velocity plus the airplane's speed) was about 4,300 feet- per-second,

"This would be more than 2,000 miles an hour, but their speed was immediately slowed down, because of air resistance. The plane was traveling about 880 miles an hour, better than 100 miles an hour faster than the speed of sound."

If the airplane had kept its original course, it would have passed by them, but its steepened dive path made it intersect the bullet's down-curving path. When it hit them, they must have been moving so slowly that the airplane overtook them at a good fraction of its own air speed, which was about as fast as many a newly fired bullet.

Post Script

Attridge continued his work with Grumman, returning to flight status 6 months later. He became the project manage for LEM-3, the first lunar module rated for human flight. It flew as "Spider" with the crew of Apollo 9.

He went on to become the president of Grumman Ecosystems which made advances that resulted in digital cameras.

I hope you enjoyed this trip through some of the history of aviation. If you enjoyed this trip, and are new to this newsletter, sign up to receive your own weekly newsletter here: Subscribe here:

Until next time, keep your eyes safe and focused on what's ahead of you, Hersch!

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.