A "Ferret" Mission

I had the honor of serving in the USAF from 1960 through 1965 as a Russian Linguist. This was during one of the most interesting periods in the history of the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

Most civilians had little knowledge of what was going on during this period, and one of the most interesting, and dangerous missions, were trying to uncover all the Soviet Union's military capabilities.

This involved all kinds of reconnaissance, from over-the-horizon radar, to voice intercept operations, to electronic surveillance, and more.

Many of these operations involved a high degree of danger. Some of us recall when a U-2 aircraft photographing Soviet bases from high altitude was shot down over the Soviet Union back in May of 1960.

But this was just one of many surveillance operations being conducted by both sides.

A "Ferret" Mission

A "Ferret" mission is one in which an attempt is made to ferret out what the enemy's capabilities are.

This particular mission took place on July 1st, 1960, exactly two months after Gary Powers flying a U2 aircraft was shot down over Sverdlovsk in the Soviet Union.

The plan was to fly an RB-47H elint aircraft from Brize-Norton Roayl Air Force Base in England northbound over the international waters of the Arctic Ocean and Barents Sea.

On board was a crew of six including the aircraft commander, Major Willard Palm, Captain Freeman B. Olmstead as pilot, and Captain John McKone as navigator.

In the converted bomber's bomb bay were an additional three "Raven" recon officers in the aircraft: Major Eugene Posa, Captain Dean Phillips, and Captain Oscar Goforth. This was Goforth's first operational mission.

Inside that bomb bay was a lot of electronic gear designed to measure the strength and weaknesses of Soviet radar and communications facilities.

The Route

International waters begin 24 miles off the coast of any country, and at 50 miles the crew were well within international waters.

From 1950 through 1960 the Soviet Union had a history of escorting and harassing (shadowing) any foreign aircraft flying over international waters near its coast.

During that period of time, there were 10 separate incidents, resulting in the loss of 75 U.S. Navy and U.S.A.F. air crewmen who were flying reconnaissance missions along the Soviet Union's borders.

Two of those incidents included a U.S. Navy bomber that was shot down over the Baltic Sea and another when a U.S.A.F. C-130 transport was lured off course by false radio beams transmitted by the Soviets.

This flight plan was for the RB-47H to depart England to fly northward and then turn east and enter the Barents Sea northeast of Norway and continue on a flight path 50 miles from the Kola Peninsula but remain over international waters.

This is a map of the intended route of the RB-47H reconnaissance aircraft on July 1, 1960.

The Intercept

As I mentioned earlier, the Soviets would "shadow" aircraft flying near the borders of the Soviet Union, even if they were flying over international waters that bordered the Soviet Union.

Soviet pilot Vasiliy Polyakov was on strip alert when he was scrambled, flying his MiG-19 fighter, assigned to the 206th Air Division, to intercept an intruding plane north of Murmansk, and west of Novaya Zemlya, in the Barents Sea.

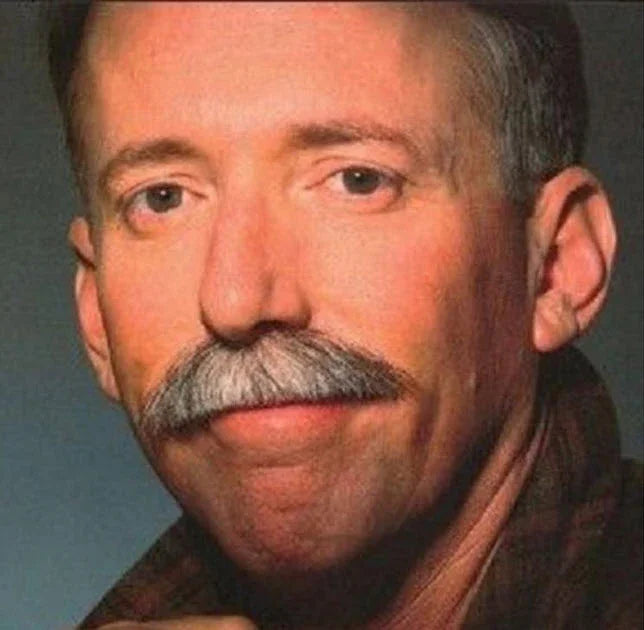

Vasiliy Polyakov, the Mig 19 fighter pilot whose aircraft was scrambled to intercept the RB-47H flying along the northern coast of the Soviet Union.

He turned toward the plane on an intercept course and passed about three miles behind it.

As he approached the aircraft he was able to identify it visually as an American bomber.

The radar course plotted by Capt. McKone called for a turn to the northeast at about 50 miles off Holy Nose Cape at the bottom of the Kola Peninsula.

However, the Soviet MiG 19 had returned and was now flying in close formation about 40 feet, off the right wing of the RB-47.

Polyakov rocked the wings of his MiG in an attempt to signal the Stratojet to land.

But when the RB-47H crew gave no response, the Soviet ground radar operator instructed Polyakov to destroy the aircraft.

The RB-47H at that time was flying at 30,000 feet with a ground speed of 425 knots and had already started its turn to the left (northeast).

Immediately Polyakov turned his MiG 19 towards the Soviet shoreline but then turned back towards the aircraft.

Polykaov opened fire on the RB-47H hitting the left wing, engines, and fuselage in his first pass, causing the aircraft to enter a downward spin.

Major Palm and Captain Olmstead were able to recover from the spin, and Olmstead attempted to maneuver and attack the MiG 19.

A Soviet MiG 19 in flight.

After some brief aerial maneuvering, Polyakov made his second firing pass, and this time the RB-47H burst into flames, rolled sharply upside down and fell into the evening clouds below.

Palm and Olmstead attempted to save the aircraft once again, but the damage was so severe the bail-out order was given.

Two of the officers, Captains McKone and Olmstead, successfully ejected and survived and climbed into their small survival rafts. Some six hours later they were picked up by a Soviet fishing vessel.

The Aircraft Commander, Palm, perished in the frigid waters, while the three reconnaissance officers were likely trapped in the aircraft and carried to the ocean's bottom.

The Aftermath

The U.S. Air Force was initially unaware that their airplane had been shot down.

Once they knew the aircraft was missing, the Air Force launched a search and rescue missing in concert with the U.S. Navy and the Soviet Union. The search lasted nearly a week after the aircraft was declared missing, but no trace was ever found.

But, ten days after the aircraft was shot down Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev announced that they had shot down the aircraft and that they had captured two of the crew members.

Khrushchev informed that the U.S. that the two captured crewmen would be tried as spies. Major Palms' body was recovered during the search and was returned to the United States approximately one month after the shootdown.

He was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetary near Washington, D.C.

Vasiliy Polyakov, the MiG pilot, later said that the shootdown was the result of Soviet internal pressure to protect its territory combined with the belief that the aircraft was headed towards a secret naval base, despite the fact that the RB-47H was operating in international airspace and over international waters.

Prison

The two pilots were housed in the dreaded Moscow Lubyanka prison and were accused by the Soviets of espionage, punishable by death.

The pilots managed to resist all Soviet efforts to obtain a confession from them, even though they were interrogated nearly every day for extended periods of time.

They were only allowed to see each twice during their incarceration and were denied visitation and access by U.S. embassy personnel.

All they told the Soviets was their names, rank, and service number.

Slowly the Soviet handlers began to allow some correspondence between the prisoners and family members.

Shortly after the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy, high-level talks between the United States and the Soviet Union began, and Premier Nikita Khrushchev extended an offer to free Olmstead and McKone.

However, there were three terms:

- 1. The announcements of the airmen's release must be made simultaneously in Washington and Moscow, with no advance news leaks;

- 2. The U.S. must publicly declare that it has discontinued its U-2 flights over Soviet territory;

- 3. The U.S. must promise not to make “international political capital” out of the prisoners' release.

The American Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Llewellyn "Tommy" Thompson, had little difficulty agreeing to the deal

After seven months of imprisonment, the pair were suddenly rushed by car to the U.S. Embassy where even the U.S. Marine guards didn't recognize the pair.

From there they were rushed to Sheremetyevo Airport to take a KLM flight out of Moscow. Unfortunately, the KLM Electra aircraft had problems taxiing out for takeoff and had to return to the terminal to have the aircraft repaired.

The two were spirited away from the airport to the embassy where they remained by pretending to be elevator repairmen. Twelve hours later the Electra was repaired and the airmen departed Moscow for Amsterdam.

From Amsterdam, the two men flew to Goose Bay, Labrador, where they spent the night, were outfitted with new uniforms, and examined by doctors who confirmed they were in good mental and physical health.

The next morning they flew from Goose Bay to Washington, D.C. aboard a Super Constellation.

They then deplaned the aircraft, tossed a brisk salute to President Kennedy, and rushed to their wives where they kissed them passionately despite all of the dignitaries waiting to talk to them.

Air Force Captains John McKone and Bruce Olmstead deplane at Andrews AFB, Maryland

Both McKone and Olmstead retired from the U.S. Air Force in October of 1983 as full colonels.

McKone died in 2013 and Olmstead in 2016. Both were interred in Arlington National Cemetary with full military honors.

Postscript

During my time in the U.S. Air Force, I served on a small island at the end of the Aleutian chain called Shemya.

After a year on Shemya, I was reassigned to Chicksands Air Force Base in Bedford, England, about one hour North of London.

I left the Air Force in 1965 and entered Michigan State University where I attained my Bachelor's Degree in Romance Languages and Political Science.

I hope you enjoyed this trip through some of the history of aviation. If you enjoyed this trip, and are new to this newsletter, sign up to receive your own weekly newsletter here: Subscribe here:

Until next time, keep your eyes safe and focused on what's ahead of you, Hersch!

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.