Surviving A Vietnam Rescue Mission

A Medal Of Honor Story

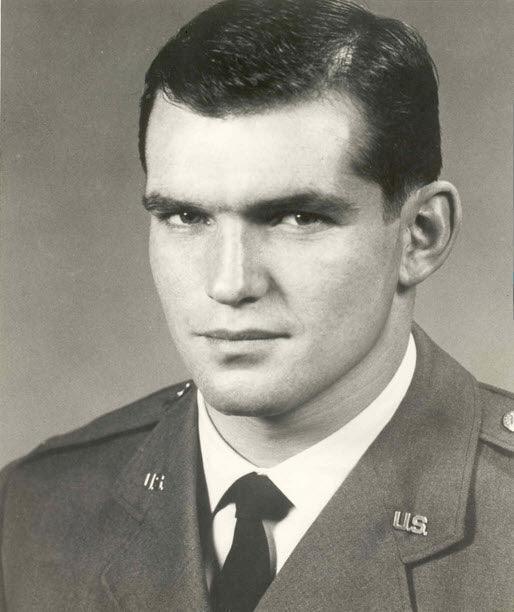

Gerald 0rren Young was born in Chicago on May 19, 1930, to Orren Vernon and Ruth Vesta Bovee Young, in Chicago, Illinois.

Not the best of times in the USA as the Great Depression had just begun and was taking its toll on many of our citizens.

He grew up during the World War II era, so like many young men his age he enlisted in the U.S. Navy at the age of 17 with a desire to do his part in serving his country. He enlisted on May 24, 1947, and the U.S. Navy trained him as an Aviation Electrician's Mate.

That training no doubt fueled his desire to learn to fly, but he was honorably discharged from the Navy on February 29th, 1952. However, On August 6, 1955 Young was back and re-enlisted in the Navy, serving until July 15, 1956, when he was accepted into the U.S. Air Force Cadet program.

On January 18, 1958 Gerald O. Young was commissioned as a 2nd Lt. and awarded his flying wings. He then completed helicopter training and his first assignment was to fly missions in support of the Marshall Islands atomic tests being conducted form July to December in 1958.

He then then served in Japan from December 1958 through January 1960, and received further training at Warren AFB, Wyoming. This was followed by stints at Dyess AFB, Texas, and then at Barksdale AFB, Louisiana, then McConnell AFB, Kansas until August of 1967.

In 1967 Young was shipped off toe Southeast Asia to fly with the 37th Aerospace and Rescue & Recovery Squadron out of the Da Nang Air Base, Republic of Vietnam.

A map of Vietnam showing the location of the Da Nang Air Base during the Vietnam War.

November 9, 1967

It was around midnight when Rescue Center called the helicopter with instructions to return to Danang.

The message was not well received by the Jolly Green Giant's crew.

Sikorsky HH-3E Jolly Green Giant. (U.S. Air Force)

The copilot, Captain Ralph Brower, said, "Hell, we're airborne and hot to trot." Staff Sergeant Eugene L. Clay and Sergeant Larry W. Maysey agreed. It was unanimous.

The pilot and rescue crew commander, Captain Gerald 0. Young, called the center back, requesting permission to continue the mission. Finally he received word that his chopper could accompany the rescue force as a backup to the primary recovery helicopter.

Captain Young's bird was part of a team that included another HH-3E, a C-130 flareship, and three US Army helicopter gunships. The armada was headed toward Khe Sanh, a small city in the northwesternmost corner of South Vietnam.

That afternoon in the jungles to the southeast of Khe Sanh, a North Vietnamese Battalion had ambushed a small US-South Vietnamese reconnaissance team. They then shot down two helicopters attempting to rescue the survivors. As evening fell, the enemy felt certain that there would be another rescue attempt either that night or early the next morning. With the survivors as bait, they would lure the rescue force into the deadly "flak trap" again.

Shortly after midnight on the 9th of November, the sounds of approaching aircraft brought feelings of hope to the survivors and anticipation to the North Vietnamese gunners. Flares from the C-130 cut through the darkness, illuminating the hillsides below. Once again the rescue effort was underway.

Low clouds and poor visibility forced the choppers to operate within range of the hostile guns, and the enemy opened fire on the gunships. Reacting swiftly, the small helicopters evaded the withering fire and answered with a stream of rockets and machine gun bullets. The bigJollys hovered nearby, waiting for a chance to make the pickup. Suddenly, the ground fire ceased.

Like motorcycles preceding a limousine, the gunships escorted the first Jolly Green Giant, strafing the silent enemy positions to protect the defenseless rescue bird. The Jolly settled slowly into place alongside a steep slope when the hillside erupted once more. The gunners fired at close range from atop a nearby ridge, and the hovering helicopter was an easy target in the ghostly flarelight. As three survivors clambered aboard, the Jolly broke out of the hover and wheeled away from the murderous barrage.

Leaking fuel, oil, and hydraulic fluid, the bullet-riddled HH-3 struggled to reach altitude. Her pilot had been forced to withdraw before two wounded Americans and the remaining survivors could be picked up. Captain Young's copilot warned the crippled ship to head for the landing strip at Khe Sanh. The Jolly would never be able to make it back to Danang. Enroute to a successful emergency landing, the pilot advised that rescue attempts should be suspended because of the intense ground fire and the low fuel state of the gunships.

Though they could easily have chosen to escort their sister ship to safety, Gerald Young and his crew decided to stay. This was the >very reason that they had volunteered to come as the backup ship. There was still a job to be done.

The crew had a plan. While Captain Young maneuvered the chopper into position, Captain Brower would direct the supporting fire of the gunships. As soon as the Jolly touched down, Sergeant Maysey would alight and lift the wounded survivors to Sergeant Clay. It would be a team effort all the way.

It took a steady hand to hover a helicopter over a flat pad in broad daylight. It would take fantastic skill and discipline to approach the hillside in the middle of the night under a hail of hostile fire. As Brower called out the enemy positions, Young eased the chopper down. He was forced to land with only one main wheel on the slope to prevent the roter blade from contacting the hill. As Sergeant Maysey leaped to the jungle floor, Sergeant Clay covered him with the Jolly's machine gun. Hanging in suspended animation awaiting the survivors, the chopper was hit by the deadly accurate fire of the North Vietnamese.

With the last of the soldiers aboard, Gerald applied full power for takeoff as enemy riflemen appeared in plain sight. They raked the bird with small arms fire and rifle-launched grenades. Suddenly the right engine sparked and exploded, and the blast flipped the HH-3 on its back and sent it cascading down the hillside in flames.

Captain Young hung upside down in the cockpit, his clothing afire. After struggling to kick out the side window and release the seat belt, he fell free and tumbled 100 yards to the bottom of the ravine. Frantically he beat out the flames, but not before suffering second and third degree burns on one-fourth of his body.

One man who had been thrown clear lay unconscious nearby, his foot afire. Young crawled to his side and smothered the flame with his bare hands. Trying to move up the hill to help those who had been trapped in the mangled helicopter, he was driven back down the slope by searing heat and whining bullets. Gerald dragged the unconscious man into the bushes, treated him for shock and then concealed himself in the ravine.

Meanwhile, the rescue effort continued. Two A-1 E Sandys arrived in the area at 3:30 a.m. The prop-driven aircraft could not make radio contact with the survivors because rescue beeper signals blocked the emergency channel, making voice transmission impossible. The Sandys circled the triangle of burning helicopters and planned a "first light" rescue effort to begin at dawn. They would fly low and slow over the crash site to attract enemy fire. Fighter bombers and helicopter gunships would then pound the hostile positions while the Sandys escorted Jolly Green Giants in for the pickup. There was no more to be done till daybreak.

As the eastern sky lightened, the Sandys began to troll slowly over the helicopter graveyard. They were elated to see Captain Young emerge from hiding and shoot a signal flare. Gerald had been trying to warn them that the North Vietnamese would probably use him as bait for their flak trap, but the beepers continued to prevent radio contact. Sensing a trap, the lead Sandy made 40 low passes, but the enemy did not respond. Had they pulled out before dawn? There was no way to be sure. At 7 a.m., the Sandys were replaced by another pair of A-IEs, and they returned to base for fuel.

For two hours there had been no opposition, and the Sandy pilots had located five survivors near one of the wrecked birds. They escorted several Army and Vietnamese Air Force helicopters in for a successful pickup. Low on fuel, the choppers departed. Things had gone smoothly since daybreak. No flak traps and no exploding choppers.

Circling back to the downed rescue ship, the Sandys again located Captain Young and the unconscious survivor. They also spotted North Vietnamese troops moving back into the area from the south. Fearing a repetition of the same nightmarish scenario, the rescue forces could not risk bringing a nearby Jolly down for a rescue attempt.

The A-ls dueled with the ground gunners inflicting heavy losses. Sandy lead laid down a smokescreen between the enemy and the survivors and led the rescue choppers in from the north.· Flanking the smokescreen, the North Vietnamese opened fire again. This time they scored, ripping the lead A-1 with armor-piercing shells and forcing him to depart for a safe area. The wingman laid down another smokescreen to shield Gerald Young and protect the rescue helicopters. In the jungle below, Gerald hid the wounded man and stole into the underbrush. He would help in the only way he could, by leading the enemy away from the crash site to take the pressure off the rescue force.

The plan worked. The enemy pursued throughout the day. Dazed and nearly in shock, he hid frequently to treat his burns. As North Vietnamese soldiers approached, Young crawled into an open field and soon found that he was moving in circles in the tall elephant grass. Certain that the enemy wanted him to contact the rescue force, he stuck by his decision not to expose the friendly aircraft to another ambush.

In the meantime, the helicopters were finally able to land a rescue party at the crash site. One survivor was rescued and the bodies of the crewmembers were recovered.

Seventeen hours after the crash and six miles from the crash site, Gerald Young finally escaped his pursuers. Only then was he able to signal a friendly helicopter. The ordeal was over.

The remaining crew members of Jolly Green 26 died in the crash. They were Captain Ralph Wayne Brower, the helicopter’s co-pilot; Staff Sergeant Eugene Lunsford Clay, flight engineer; Sergeant Larry Wayne Maysey, Pararescueman. The soldiers that “Jolly 26” had just rescued, Special Forces Master Sergeant Bruce Raymond Baxter and Specialist 4 Joseph George Kusick, both of U.S. Army Reconnaissance Team UTAH, were also killed.

Captain Brower, Staff Sergeant Clay and Sergeant Maysey were each posthumously awarded the Air Force Cross for “extraordinary heroism” during the rescue.

A Medal of Honor was presented to Young by President Lyndon B. Johnson on May 14, 1968, at the Pentagon, Washington, DC.

The Medal of Honor Citation

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. Capt. Young distinguished himself while serving as a helicopter rescue crew commander. Capt. Young was flying escort for another helicopter attempting the night rescue of an Army ground reconnaissance team in imminent danger of death or capture. Previous attempts had resulted in the loss of two helicopters to hostile ground fire. The endangered team was positioned on the side of a steep slope which required unusual airmanship on the part of Capt. Young to effect pickup. Heavy automatic weapons fire from the surrounding enemy severely damaged one rescue helicopter, but it was able to extract three of the team. The commander of this aircraft recommended to Capt. Young that further rescue attempts be abandoned because it was not possible to suppress the concentrated fire from enemy automatic weapons. With full knowledge of the danger involved, and the fact that supporting helicopter gunships were low on fuel and ordnance, Capt. Young hovered under intense fire until the remaining survivors were aboard. As he maneuvered the aircraft for takeoff, the enemy appeared at point-blank range and raked the aircraft with automatic-weapons fire. The aircraft crashed, inverted, and burst into flames. Capt. Young escaped through a window of the burning aircraft. Disregarding serious burns, Capt. Young aided one of the wounded men and attempted to lead the hostile forces away from his position. Later, despite intense pain from his burns, he declined to accept rescue because he had observed hostile forces setting up automatic-weapons positions to entrap any rescue aircraft. For more than 17 hours he evaded the enemy until rescue aircraft could be brought into the area. Through his extraordinary heroism, aggressiveness, and concern for his fellow man, Capt. Young reflected the highest credit upon himself, the U.S. Air Force, and the Armed Forces of his country.

Watch this video about Capt. Young:

Surviving A Vietnam Rescue Mission - A Medal of Honor Story.

Postscript

Young continued his career in the military and earned a bachelor's degree from the University of Maryland while he was stationed in Washington, D.C.

He met his wife, Yadi, during a trip to Costa Rica. They were married in 1972 and had a daughter they named Melody. Young retired in 1980 at the rank of lieutenant colonel.

He and his wife moved to a 30-acre farm in Anacortes, Washington, where Young spent the next decade speaking about his military career to students, ROTC units and at public events.

Young died on June 6, 1990, of a brain tumor. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. The town of Anacortes dedicated a park in his honor.

I hope you enjoyed this trip through some of the history of aviation. If you enjoyed this trip, and if you are new to this newsletter, sign up to receive your own weekly newsletter here: Subscribe here!

Until next time, keep your eyes safe and focused on what's ahead of you, Hersch!

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.