The First Cold War Crisis

On May 8, 1945, Germany unconditionally surrendered to the Allies, bringing to an end World War II in Europe.

The last shots fired in anger in Europe were on May 11, 1945.

This also brought to an end the incredible destruction of much of Germany.

The European Theater in WWII

World War II brought together a number of countries to defeat the Germans, among them the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union.

Cooperation between the Allies required tough compromises, so once the war in Europe was over, it was time to divvy up the spoils of war.

Between July 17, 1945, and August 2nd, 1945, the leaders of the Big Three Allies (United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union) gathered for a conference in Potsdam, Germany.

It was here that the tough negotiations were made.

Although the Allies remained committed to fighting a joint war in the Pacific, the lack of a common enemy in Europe led to difficulties in reaching a consensus concerning the postwar reconstruction of the European continent.

The major issue was how to handle Germany.

At the previous Yalta conference, the Soviets had pressed for heavy postwar reparations from Germany, half of which they insisted would go to the Soviet Union.

The Allies agreed to divide Germany, including the city of Berlin, into four (4) sections. The sections were divided among France, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States.

It was agreed that all the sections of Germany would be governed as a single economic unit in anticipation of their eventual reunification.

The City of Berlin was also divided up into four (4) sections, one section each to France, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States.

While Roosevelt had acceded to such demands, Truman and his Secretary of State, James Byrnes, were determined to mitigate the treatment of Germany by allowing the occupying nations to exact reparations only from their own section of occupation.

The leaders of the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union, who, despite their differences, had remained allies throughout the war but never met again collectively to discuss further cooperation in postwar reconstruction.

After the victory over Germany, however, the wartime cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union soon faded.

Mutual distrust ruled the relationship between the two countries and nowhere was this more evident than in the difficulties over the occupation of Germany.

A Divided City

The city of Berlin was located approximately 100 miles inside the section of Germany awarded to the Soviet Union.

The biggest immediate issue was how to provide food and necessities for all of the residents of Germany because of its almost total destruction.

Most of the food supply available at that time in Europe was being produced by the Soviet Union, giving Joseph Stalin a wedge issue.

At the start, the Western powers relied upon the goodwill of the Soviets, rather than a formal agreement, to allow them unlimited access to the Allied sections of Berlin.

Initially, access was allowed by rail, road, and through limited approved air routes from West German cities, and requests for further expansion were denied.

In addition, the Soviet Union soon started to limit deliveries of goods (including agricultural products) into other sectors.

This went on for several years.

The Marshall Plan

The Soviet view of post-war Germany was that it should remain an economically weak and agricultural socialist state within the Soviet sphere of influence.

The Soviets stripped its sector of manufacturing equipment in an effort to garner part of the reparations it felt entitled to.

In 1946, the United States and Great Britain merged their occupation zones and established a new German currency; and in 1947, the U.S. Government began a massive aid program under the Marshall Plan to rebuild shattered post-war Germany.

On June 24, 1948, the Soviet Union took action against the West's policies by blocking all road access between West Germany and West Berlin, effectively cutting off the city's occupation zones from the British, French, and American forces responsible for maintaining them.

The administrators of the western zones had no agreement with the Soviet Union that required the latter to allow ground access to the city through Eastern Germany, but they did have an agreement on air access.

The Berlin Airlift

This left the Allies with no other option than to organize a joint air operation to take supplies into Berlin.

Rationing in the city was introduced to reduce the requirements for supplies, but there was still a massive need for supplies of both food and fuel.

It was estimated that it would require approximately 5,000 tons of food and fuel per day.

To put this into perspective, the Avro York (the largest aircraft used by the UK RAF) could only carry about 10 tons per flight.

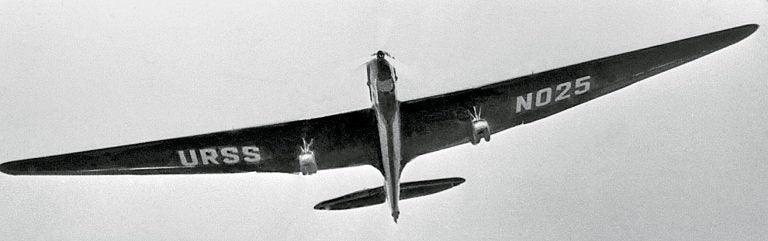

An RAF Avro York C1 in flight bound for Berlin in 1948.

Postwar cuts had reduced the size of both the military and the air force, so this was no easy task to undertake.

The U.S. military began flights on June 25, 1948, with the UK RAF starting on June 29, 1948.

The Aircraft

The U.S. military operated a number of C-47 aircraft (the military version of the venerable Douglas DC-3), along with their four-engine C-54 aircraft (the military version of the Douglas DC-4).

The UK RAF operated a large fleet of Dakotas (their military version of the Douglas DC-3), a smaller number of the Avro York C1 aircraft, along with a number of Short Sunderland flying boats wich were based in the Havel River.

A UK RAF Sunderland flying boat unloading cargo during the Berlin airlift.

Initially, operations landed at Tempelhof Airport in Berlin, but in November of 1948, the Berlin Tegel airport joined the airlift operation.

A C-54 Skymaster aircraft on final to Tempelhof Airport in Berlin.

By July of 1948, it became clear that the airlift would be a long-term operation and that airlift capacity would need to increase further.

U.S. Air Force General William H. Tunner was brought in to manage operations at Tempelhof better.

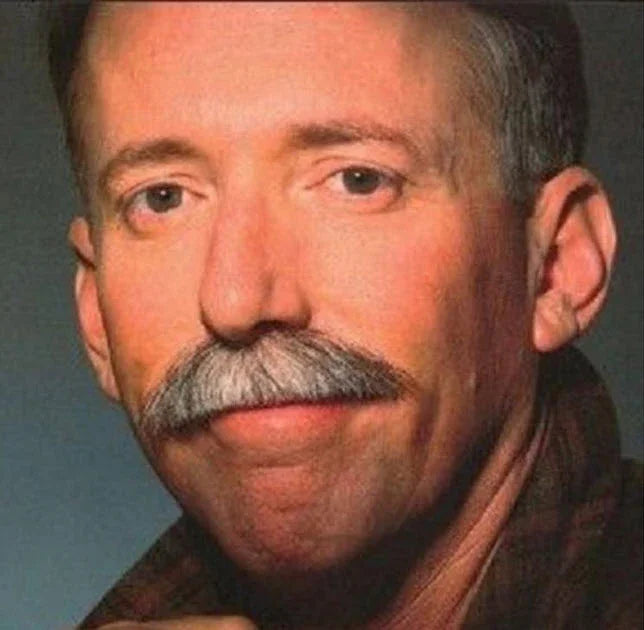

General Tunner in his operations center at Tempelhof Airport in Berlin.

Operationally, a single point of control was established for all air forces involved.

Larger aircraft, specifically the C-54 Skymaster, were used to bring in more cargo per landing.

Aircraft approach and separation procedures were altered to increase flow and safety, with no stacking of aircraft and all aircraft flying under IFR Instrument Flight Rules) flight rules.

These changes saw Tempelhof handling more than 1,400 flights per day at the peak of the airlift.

U.S. Air Force C-47 Skytrain aircraft lined up at Tempelhof Airport unloading supplies.

Flying The Corridors

Pilots flying in the corridors encountered numerous problems; one was the erratic German weather. The weather changed so often that it was not uncommon to leave a base in West Germany under ideal conditions only to find impossible conditions in Berlin.

What made it even more treacherous was the approach to Tempelhof.

In order to land there, a pilot had to literally fly between the high-rise apartment buildings at the end of the runway so he could land.

A second runway required a steep drop over a building in order to land soon enough so that there was enough runway for braking.

All these conditions, plus a fully loaded C-54 with a 10-ton cargo load, were more than enough for any pilot to handle, especially during the German winter.

Unfortunately, that wasn't all the pilots had to deal with.

The Soviets constantly harassed the pilots during the operation.

Between 10 August 1948 and 15 August 1949, there were 733 incidents of harassment of airlift planes in the corridors.

Acts of Soviet pilots buzzing, close flying, shooting near, not at airlift planes were common. Balloons were released in the corridors, and flak was not unheard of.

Radio interference and searchlights in the pilots' eyes were all forms of Soviet harassment in the corridors.

However, this did not stop the pilots, and the planes kept chugging on in.

In spite of all these acts of harassment, no aircraft was shot down during the operation.

That would have started a war, and the Soviets did not want that, especially with U.S. B-29s stationed in England. Although the B-29s that were there were not atomic bomb capable, the Soviets did not know that and did not want to find out.

So, the airlift went on.

American C-54s were stationed at Rhein-Main, Wiesbaden, Celle, and Fassberg in the British Sector.

The British flew Lancasters, Yorks, and Hastings aircraft. They even used Sunderland Flying Boats to deliver salt, using Lake Havel in the middle of Berlin as a base.

Every month the tonnage increased and soon exceeded the daily requirements.

Every day, tonnage records were being set, and the constant drone of airplanes overhead was music to the Berliner's ears.

Eventually, rations were increased, and life in West Berlin was improving.

There was an obstacle in the way on the approach to Tegel Airport, however, despite pleas to remove the Soviet-controlled radio tower, they refused to remove it.

On November 20, 1948, French General Jean Ganeval decided if the would not take it down, he would simply blow it up.

So, on December 16, dynamite was used, and the tower fell.

Obstacle removed.

Conclusion

At the height of the airlift, one airplane reached Berlin every 30 seconds.

A total of 101 fatalities were recorded as a result of airlift operations, including 40 Brits and 31 Americans.

Seventeen American and eight British aircraft crashed during the operation, causing most of the deaths.

I hope you enjoyed this trip through some of the history of aviation. If you enjoyed this trip, and are new to this newsletter, sign up to receive your own weekly newsletter here: Subscribe here.

Until next time, keep your eyes safe and focused on what's ahead of you, Hersch!

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.