The Provider

Heros come in all sizes, and in the military many heros come forth at just the right time with the right skills and the desire to serve.

This story is about one such hero - Lt. Col. Joe M. Jackson/span>

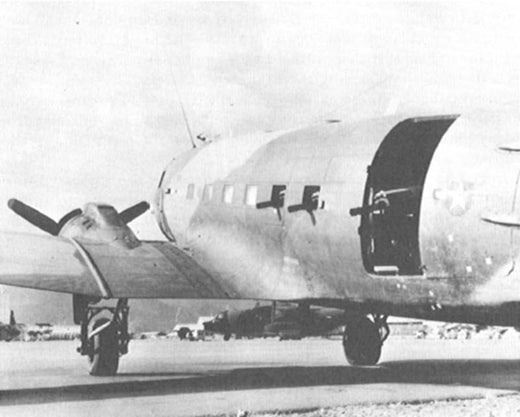

The Aircraft

The Fairchild-Hiller built C-123 Provider carried 60 troops or 12 tons of cargo. Pallets and vehicles were rapidly loaded through a tail ramp in the aft fuselage, and paratroopers jumped from smaller doors on either side of the aircraft. With a full payload, the Provider weighed over 30 tons.

Two small jets were added to later models of the twin-engine, prop-driven bird for improved takeoff performance and load-carrying capability. The jets were fired up for takeoff, allowing a short ground roll and a quicker climb to altitude. The steep climbout minimized the three-man crew's exposure to groundfire.

The Providers in Vietnam were painted with a camouflage design to give the enemy gunner less time to aim and fire at the cargo ships.

Flying at a top speed of 230 miles per hour, the C-123 often flew many sorties in a single day, leapfrogging from one dirt strip to the next to supply remote Army outposts.

A line drawing of the Fairchild C-123B Provider.

Specifications:

- Wingspan: 110 feet 0 inches;

- Length: 76 feet 3 inches;

- Height: 34 feet 1 inch;

- Empty weight: 35,366 pounds;

- Gross weight: 51,576 pounds;

- Engines: 2 Prat & Whitney R-2800-99W Double Wasp 18 cylinder air cooled radial piston engines;

- Maximum speed: 228 mph;

- Range: 1,035 miles at gross weight;

- Service ceiling: 21,100 feet on one engine.

A photograph of the cockpit or a C-123K Provider.

The Man

Lt. Col. Joe M. Jackson was born on March 14, 1923 and enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1941 to become an aircraft mechanic.

After serving as a crew chief in a B-25 bomber unit, Sergeant Jacckson began pilot training, earning his wings and commission in 1943. By the time he was ready the Korean War was at hand, and during that war flew 107 fighter missions while earning the Distinguished Flying Cross.

He was one of the first pilots to fly the U-2, and after 20 years as a fighter pilot he was assigned to transport duty. The 45 year old office won the Medal of Honor in Vietnman in 1968 and flew 296 missions during his combat tour.

A Hero's Story

What follows is the incredible story of Col. Jackson's heroism.

May 12, 1968

Not many pilots looked forward to a flight check. As inevitable as desk jobs and remote assignments, flight checks were something you learned to live with. Twice a year the Air Force wanted to be reassured that you still had the skills and knowledge to accomplish the mission effectively and safely. It mattered little if you were a colonel or a lieutenant, if you'd flown the flight check profile many times before, or if the flight examiner was your best friend. You knew that you were expected to do a first-rate job and that the examiner would write an objective report on your performance. Not really something to get sweaty palms over, but never taken lightly either. Check rides in a combat zone? Of course. The Air Force's mission was to fly and fight and do them professionally.

On May 12; 1968, C-123 number 542 lined up on the runway at Danang Air Base. The Provider was scheduled to swing north toward the Demilitarized Zone and back down the coast toward Chu Lai, stopping enroute to resupply several outposts. The cargo bird could carry a good load and still land and take off from the temporary jungle

strips.

Lieutenant Colonel Joe M. Jackson was at the controls and Major Jesse Campbell was the flight examiner in the right seat. Technical Sergeant Edward M. Trejo and Staff Sergeant Manson L. Grubbs rounded out 542's crew.

As he guided the Provider into the air and retracted the gear and flaps, Joe Jackson remembered that it was Mother's Day. But thoughts of family tnust wait. He had· supplies to deliver and a check ride to pass.

The weather along the coast was good and the mission went well. Joe had successfully completed all flight-check requirements when the crew got an unexpected message to return to home base.

Meanwhile, 45 miles to the southwest of Danang, near the Laotian border, a massive airlift operation was underway at Kham Due. A steady stream of C-123s and C-130s shuttled into the isolated Special Forces camp to evacuate 1,000 friendly troops. Vastly outnumbered, they had been under siege by a communist force for three days. Now the outpost was in danger of being overrun.

Map of Indo China showing area where the Cargo and Gunships operated in Vietnam.

Lieutenant Colonel Jackson and his crew were briefed at Danang on the emergency rescue operation, and they were airborne again in less than an hour, heading southwest toward Kham Due. As they flew inland the weather deteriorated, but the C-123 entered a holding pattern south of the camp at 3:30 p.m.

The evacuation was a hectic operation. An airborne command post controlled the flow of cargo planes into the short strip that lay unprotected on the valley floor. Forward air controllers directed fighterbombers against Vietcong positions surrounding the runway. As number 542 moved closer to the camp, smoke and flames from exploding ammunition dumps and tracers from enemy weapons were clearly visible, even from an altitude of 9,000 feet.

Joe and his crew relaxed as the radio chatter confirmed that the last suvivors had been rescued. Now the command post directed the fighters to destroy the camp and the enemy with it. But something was wrong. An animated voice on the radio warned that three US airmen had been left behind.

Attempts to contact the three combat controllers failed, and the command post asked the C-123 ahead of number 542 to land and try to pick them up. As the Provider approached the runway, she drew flak like a magnet. The fighters tried to protect the slow-moving bird by strafing the jungles as the enemy opened up with machine guns, mortars, and recoilless rifles. The Americans had snatched 1,000 men from under the Vietcong's nose, and the Cong wanted someone to pay the price.

As the aircraft touched down, she came under intense fire from positions on the· edge of the runway. Seeing no chance to locate the three airmen, let along pick them up, the pilot jammed the throttles full forward and prepared for takeoff. Just before liftoff the crew spotted the three combat controllers crouching in a ditch bordering

the runway, but it was too late to stop. The C-123 lifted off through a volley of bullets. Low on fuel, she headed for home base.

/p>

Joe Jackson had an answer for the question even before it was asked. Would he? "There wasn't any question about it. There wasn't any decision to make. Of course, we would make the attempt." Jesse Campbell radioed, "Roger. Going in."

Technical Sergeant Mort Freedman spoke for the combat controllers, describing how he, Major John Gallagher, and Sergeant Jim Lundie reacted when the last Provider took off, leaving the three-man team behind. "The pilot saw no one left on the ground, so he took off. We figured no one would come back and we had two choices. Either be taken prisoner or fight it out. There was no doubt about it. We had 11 magazines left among us, and we were going to take as many of them with us as we could."

Lieutenant Colonel Jackson called on his fighter-pilot experience and decided to try a new tactic. He knew the Vietcong gunners would expect him to follow the same flight path as the other cargo birds. What if he could take an elevator straight down into the valley?

Nine thousand feet high and rapidly approaching the landing area, he pointed 542's nose down in a steep dive. The book said you didn't fly transports this way. But the guy who wrote the book had never been shot at. Joe recalls, "I had two problems, the second stemming from the first. One was to avoid reaching 'blow up' speed, where the flaps, which were in full down position for the dive, are blown back up to neutral. If this happened, we would pick up even more speed, leading to problem two, the danger of overshooting the runway."

Taken by surprise, the enemy gunners reacted in time to open fire as the diving Provider neared the strip. Joe coaxed her nose up, breaking the dizzying descent just above the treetops, one quarter of a mile from the end of the runway. He barely had time to set up a landing attitude as the Provider settled toward the threshold.

The debris-littered runway looked like an obstacle course. Just 2,200 feet from the touchdown point a burning helicopter blocked the way. He knew he would have to stop in a hurry, but Joe Jackson decided against using reverse thrust to slow the bird. Reversing the engines would automatically shut off the two jets that would be needed for a minimum-run takeoff. He stood on the brakes like no Indianapolis

driver ever had.

The only photo ever to capture actions leading to a Medal of Honor - Lt. Col. Joe M. Jackson.

Number 542 skidded to a stop just before reaching the gutted helicopter. Three men scrambled from the ditch, reaching the airplane as Sergeant Grubbs lowered the rear door. He and Sergeant Trejo pulled them aboard.

In the meantime, Major Campbell spotted a 122-millimeter rocket shell, and the two pilots watched in horror as it came to rest just 25 feet in front of the nose. Luck was still on their side. The deadly projectile did not explode.

Joe taxied around the shell and rammed the throttles t6 the firewall. "We hadn't been out of that spot ten seconds when mortars started dropping directly on it," he remembers. "That was a real thriller. I figured they just got zeroed in on us, and that the time of flight of the mortar shells was about ten seconds longer than the time we sat there taking the men aboard." Dodging shell craters, 542 accelerated down the runway.

Just ahead tracers illuminated a murderous crossfire, but there was no turning back. "We were scared to death," Jackson said.

The ship broke ground, slowly picking up speed and climbing toward intense fire from the far end of the runway. Nothing to do now but press on, wishing that they could take the same elevator out of there. At last Kham Due was behind them.

Number 542, a peaceful cargo bird once more, landed at Danang at 5:30 p.m. with her four-man crew and three passengers. Miraculously, she had not taken one hit! "I will never understand that," is Lieutenant Colonel Jackson's comment. "And to think, I only flew that day because it seemed like a good time to get a needed' flight check!"

Sergeant Freedman added a simple postscript. "If they hadn't gone in, there is no doubt that we would have been killed or captured." Mother's Day 1968, Vietnamese style, was over.

The Medal of Honor Awarded

A photograph of President Johnson (facing Lt. Col. Jackson) congratulates four Medal of Honor recipients.

I hope you enjoyed this trip through some of the history of aviation. If you enjoyed this trip, and if you are new to this newsletter, sign up to receive your own weekly newsletter here: Subscribe here!

Until next time, keep your eyes safe and focused on what's ahead of you, Hersch!

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.