Kenneth A. Walsh, Lt. Col. USMC, WWII

On a cold, snowy November 24th day in 1916, in Brooklyn, NY, Ambrose and Irene Walsh were blessed with a baby boy whom they named Kenneth Ambrose Walsh, the baby brother to his sister, Claire Walsh.

Unfortunately, when Kenneth was only 7 years old, his father passed away, and the family moved to Harrison, New Jersey, close to the Newark Airport. Walsh would often times ride his bike to the airport, lean on the airport fence, and watch small airplanes come and go.

Kenneth Walsh was not only a good student, but he became an outstanding track star for his high school, Dickinson High School, from which he graduated in 1933.

On December 15, 1933, Kenneth A. Walsh, at the age of 17, enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps. Upon acceptance into the Corps, Walsh was sent to the Marine Corps Recruit Depot at Parris Island, South Carolina, for Marine basic training.

Following his recruit training Walsh was sent to another base where he learned to become an aircraft mechanic and radioman at Marine Corps Base in Quantico, Virginia. Walsh did not want to be an aircraft mechanic - he wanted to be the one in the air and not one on the ground. Then, in March of 1936, Walsh was transferred to Naval Air Station in Pensacola, Florida, for pilot training.

While still holding the USMC rank of Private, he attended flight training, and upon earning his Wings of Gold as a U.S. Naval Aviator, on April 26, 1937, was promoted to the rank of Corporal.

Walsh then spent the next four years flying scout observation float planes off of three different aircraft carriers. This was followed with an assignment to the newely formed Marine Fighter Attack Squadron 121 (VMF-121) which was originally based in South Carolina.

In 1940, Walsh married Beulah Mae Barinott, and together they had two sons, Kenneth Jr. Walsh and Thomas Walsh. At that time Walsh held the rank of Master Technical Sergeant as a pilot, before the outbreak of World War II.

In December of 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands. On May 11, 1942, Walsh was promoted to the rank of Marine Gunner (the equivalent to Warrant Officer), followed by an assignment to Marine Aircraft Group 12 (MAG-12) , 1st Marine Aircraft Wing. Marine Aircraft Group twelve was activated at Camp Kearney, California, on March 1, 1942.

By Septermber of 1942, the U.S. was in the thick of the fighting in World War II in the Pacific Theater. Walsh was assigned to VMF-124 because he was one of the most experienced pilots in the USMC's first Vought F4U Corsair squadron.

F4U-1 CorsairSpecifications:

- Crew: 1;

- Length: 33 feet 4 inches;

- Wingspan: 41 feet 0 inches;

- Height: 16 feet 1 inch;

- Powerplant: Pratt & Whitney R-2800-8 Double Wasp 1,000 hp;

- Speed: 417 mph or 362 knots;

- Service ceiling: 36,900 feet;

- Range: 1,015 miles;

- Max Takeoff Weight: 14,000 pounds.

In October 1942 Walsh was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant. Because of his prior aircraft carrier duty, Walsh was one of a handful of Marine pilots qualified as an aircraft carrier landing signal officer.

Marine Fighter Squadron VMF-214 in front of an F4U Corsair Black Sheep squadron led by Maj. "Pappy" Boyington.

The Vought F4U Corsair was designed with a bomber-sized propellor which was longer than 13 feet, and as a result the Corsair was designed with the inverted gull wings and long nose which were necessary to give the prop ground clearance.

Corsair Pilots from VMF-214 of the Black Sheep squadron showing off.

Shortly thereafter VMF-214 was deployed to the Pacific where it served from December 1942 unti cessation of hostilities in late 1945. In January 1943 Walsh's unit, VMF-214, was sent to Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, and the pilots were immediately thrust into combat.

On April 1, 1943, Walsh shot down his first three Japanese aircraft, followed on May 13, 1943 by another two Japanese aircraft shot down, becoming the very first Corsair fighter ace. Walsh by now had been promoted to 1st Lieutenant.

Walsh's prowess in the skies continued to grow throughout the summer, and by August Walsh and his squadron were conducting aerial combat missions in the skies over the Central Solomon Islands, well to the east of Papua New Guinea.

By Aug. 15, 1943, U.S. troops were trying to take over the small island of Vella Lavella, while Japanese aircraft were trying to thwart those efforts by bombing U.S. ground forces and the equipment that was flowing in.

Walsh cut that attempt short by diving his aircraft into an enemy formation that vastly outnumbered his own by 6 to 1. He managed to take out two Japanese dive bombers and one fighter aircraft.

During the melee, Walsh's Corsair was hit by 20mm cannon fire, which blew holes into a wing and the fuel tank. The plane was badly damaged, but he still managed to fly it back to safety and land.

About two weeks later, on Aug. 30, Walsh and three others from his squadron were called upon to escort some Army B-24 Liberators on a strike against Kahili, an enemy airfield on the island of Bougainville.

After refueling at a forward air base before the attack, the four aircraft took off again to rendezvous with the bombers. But as they did, Walsh's aircraft began acting up and he was forced to make an emergency landing on the small island of Munda.

Thankfully, he had a friend in charge of the Allied airfield there, so he was able to quickly replace his Corsair with another, then rejoin the planned flight to Kahili. Walsh had yet to link up again with his escort group when he ran into about 50 Japanese Zeros which were swarming the B-24s his goup was escorting.

The Allied aircraft were busy doing their bombing runs and needed to be defended, so Walsh didn't hesitate. Even though he was alone, he took the fight to the enemy aircraft, "striking with relentless fury," according to his Medal of Honor citation.

Eventually, other American pilots appeared to help alleviate some of the burden Walsh had been facing. Walsh took stock of his situation and subsequently destroyed four hostile fighters.

By then, however, his aircraft had been badly damaged, so he had to disengage from the fighting. As Walsh tried to get away from the action, more Zeros continued to use him as a target until his fellow pilots sent them scattering.

As his aircraft lost all propulsion, Walsh was forced to land off Vella Lavella, which had just been liberated by U.S. troops the week before. He was later picked up by Navy Seabees, who borrowed a boat to get him after seeing his aircraft splash down into the sea.

Walsh returned to the U.S. about two months later, but his leadership and daring skill as an ace pilot inspired the men with him to keep up the fight. For his bravery, Walsh received the Medal of Honor on Feb. 8, 1944, from President Franklin D. Roosevelt, during a ceremony in the White House Oval Office. That same month, he was promoted to captain.

The Medal of Honor

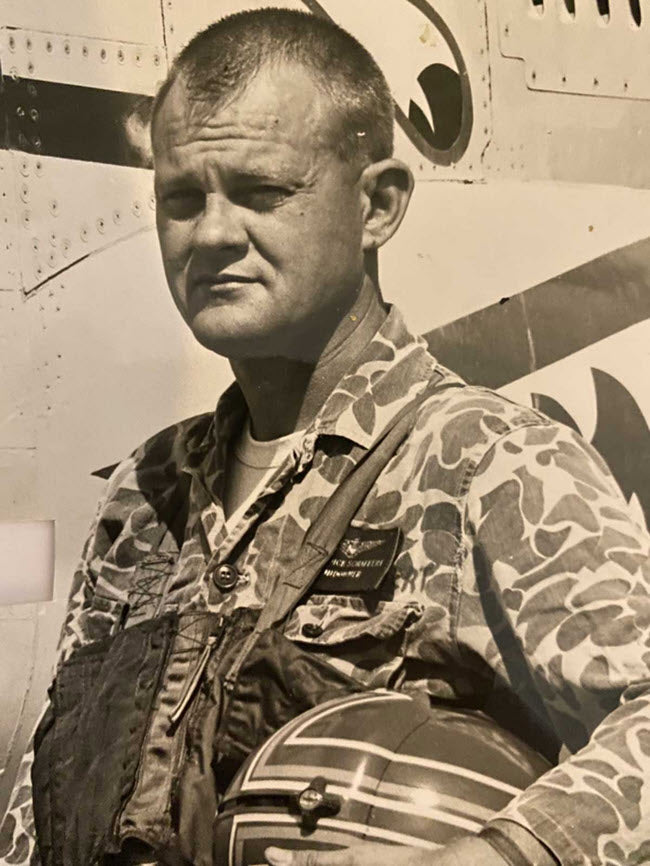

Photograph of Lt. Col Kenneth Walsh, USMC, WWII Medal of Honor Recepient.

Details:

- Rank: First Lieutenant (Highest Rank: Lieutenant Colonel)

- Conflict/Era: World War II

- Unit/Command:

Marine Fighting Squadron 124, Marine Air Group 12,

1st Marine Air Wing - Military Service Branch: U.S. Marine Corps

- Medal of Honor Action Date: August 30, 1943

- Medal of Honor Action Place: Vella Lavella & Kahili, Solomon Islands

Citation

For extraordinary heroism and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty as a pilot in Marine Fighting Squadron 124 in aerial combat against enemy Japanese forces in the Solomon Islands area. Determined to thwart the enemy's attempt to bomb Allied ground forces and shipping at Vella Lavella on 15 August 1943, 1st Lt. Walsh repeatedly dived his plane into an enemy formation outnumbering his own division six to one and, although his plane was hit numerous times, shot down two Japanese dive bombers and one fighter. After developing engine trouble on 30 August during a vital escort mission, 1st Lt. Walsh landed his mechanically disabled plane at Munda, quickly replaced it with another, and proceeded to rejoin his flight over Kahili. Separated from his escort group when he encountered approximately 50 Japanese Zeros, he unhesitatingly attacked, striking with relentless fury in his lone battle against a powerful force. He destroyed four hostile fighters before cannon shellfire forced him to make a dead-stick landing off Vella Lavella where he was later picked up. His valiant leadership and his daring skill as a flier served as a source of confidence and inspiration to his fellow pilots and reflect the highest credit upon the U.S. Naval Service.

During World War II, fighter pilot Walsh became a flying legend. Considered by many airmen to be one of the toughest and most aggressive Marine combat pilots, Walsh was credited with 21 Japanese enemy airplanes destroyed. He was the fourth highest combat ace in World War II.

Military Career Post WWII

Walsh remained in the Marine Corps after the war. In March 1946, he was assigned to the Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics, then he returned to the fleet for a few more years before the Korean War broke out. In 1950, he was sent to the Korean peninsula with Marine Air Group 25.

During the Korean War, Walsh was assigned to VMR-152 transport squadron and flew combat missions between October 8, 1950 until July 23, 1951. In April 1952 he was promoted to the rank of Major.

In October 1958 Walsh was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. On February 1, 1962, Walsh retired from the Marine Corps and was active in the Congressional Medal of Honor Society.

According to an article in the 1994 Orange County Register, Walsh continued to work with veterans' groups and wrote for military publications. He also sought out several Japanese pilots, some who may have even shot him down.

"There is a camaraderie among pilots," he told the newspaper. "You respect the skills of the other guy. Most have a code of ethics. I would never strafe a downed pilot. Most of them wouldn't, either."

Walsh died on July 30, 1998, of a suspected heart attack at his home in Santa Ana, California. According to his obituary in the Orange County Register, he was preparing to head to an air show in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, where he and three other Medal of Honor recipients were to be honored.

Walsh is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. His Medal of Honor can be found at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola.

I hope you enjoyed this trip through some of the history of aviation. If you enjoyed this trip, and if you are new to this newsletter, sign up to receive your own weekly newsletter here: Subscribe here!

Until next time, keep your eyes safe and focused on what's ahead of you, Hersch!

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.